Conflict Resolution Playbook: How Agentic AI Systems Detect, Negotiate, and Resolve Disputes at Scale

When you deploy dozens or hundreds of AI agents across your organization, you're not just automating tasks. You're creating a digital workforce with its own internal politics, competing priorities, and inevitable disputes. The question isn't whether your agents will come into conflict. The question is whether you've designed a system that can resolve those conflicts without grinding to a halt or escalating to human intervention every time.

Most organizations are discovering this reality the hard way. They launch a pilot with three agents, see promising results, and decide to scale. By the time they reach 20 agents, they're already drowning in exceptions, deadlocks, and agents waiting on manual approvals. The problem isn't the agents themselves. It's that conflict resolution was treated as an afterthought rather than a core design principle.

This post lays out a practical approach for building conflict resolution into your agentic AI systems from day one. We'll explore the types of conflicts that emerge in multi-agent environments, examine different resolution strategies, and provide a playbook for designing systems that can negotiate, arbitrate, and learn from disputes without constant human oversight.

Why Conflict Resolution Matters in an Agentic World

Conflict is built into the architecture of any multi-agent system. It's not a bug or a failure mode. It's the natural result of deploying autonomous agents with different objectives, shared resources, and overlapping authority.

Consider what happens when you deploy agents across multiple business functions. Your sales agent is optimized to close deals quickly and maximize revenue. Your finance agent is designed to minimize risk and ensure compliance. Your supply chain agent is balancing cost against resilience. These agents don't have competing goals because someone made a mistake in their design. They have competing goals because they're doing exactly what they were built to do.

The same conflicts exist between human employees every day. The difference is that humans have evolved sophisticated (if imperfect) ways of negotiating, compromising, and escalating disputes. We have organizational hierarchies, informal networks, and cultural norms that guide us toward resolution. AI agents operating at machine speed don't have those luxuries.

Traditional enterprise escalation models break down completely in agentic environments. The "schedule a meeting and hash it out" approach doesn't work when agents are making hundreds of decisions per hour. The "escalate to a manager" pattern doesn't scale when you have agents operating across dozens of workflows simultaneously. And the "just follow the policy manual" solution fails when agents encounter novel scenarios that policy never anticipated.

The core premise of effective agentic systems is this: conflict resolution must be designed into the architecture, not improvised after deployment. It needs to be as automated, scalable, and intelligent as the agents themselves.

What "Conflict" Looks Like in Agentic Systems

Before you can resolve conflicts, you need to recognize them. In agentic AI systems, conflicts manifest in several distinct forms, each requiring different resolution approaches.

Goal conflicts occur when agents pursue competing objectives. A marketing agent wants to maximize customer acquisition, even if it means higher CAC. A finance agent wants to maintain strict budget discipline. Both agents are performing correctly according to their design, but their objectives are incompatible in specific contexts.

Resource conflicts emerge around constrained assets. Two agents need access to the same API that has rate limits. Multiple agents want to allocate budget from the same pool. Agents compete for compute resources during peak demand periods. These conflicts are often time-sensitive and require fast resolution to avoid workflow bottlenecks.

Policy conflicts arise when agents operate under different governance frameworks. A customer service agent trained on maximizing satisfaction may offer solutions that violate compliance policies. A data analysis agent may want to access information that privacy policies restrict. These conflicts typically involve hard constraints that can't be negotiated away.

Interpretation conflicts happen when agents have semantic or contextual disagreements. One agent interprets "urgent" as "complete within 24 hours" while another interprets it as "prioritize above all else." These conflicts often reveal ambiguities in how agents are instructed or how they understand shared terminology.

Let's look at some common enterprise scenarios where these conflicts play out:

A sales agent negotiating a contract wants to offer a 20% discount to close a deal before quarter-end. The finance agent has flagged this customer's industry as elevated risk and wants stricter payment terms. The sales agent argues that the deal is strategic. The finance agent counters that risk policy doesn't have a "strategic" exception. Without a resolution mechanism, the deal stalls or requires manual intervention.

Supply chain agents face this constantly. One agent is optimized to minimize inventory costs through just-in-time delivery. Another agent is designed to ensure supply resilience by maintaining buffer stock. When component prices spike, these objectives create a direct conflict. The cost-optimization agent wants to delay purchases. The resilience agent wants to lock in supply. Both are right according to their mandates, but they can't both execute.

Customer-facing agents navigate especially delicate conflicts. A personalization agent has learned that a particular customer responds well to aggressive upselling. A compliance agent has determined that the customer's jurisdiction requires explicit opt-in for promotional communications. The personalization agent has higher conversion data. The compliance agent has regulatory authority. How do they resolve this without human judgment on every interaction?

The Conflict Resolution Lifecycle

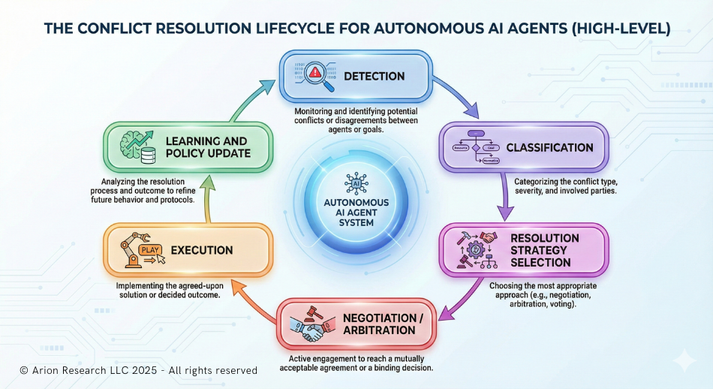

Effective conflict resolution in agentic systems follows a structured lifecycle. Understanding this cycle helps you design systems that can detect problems early and resolve them efficiently.

Detection is the first critical phase. Agents must recognize when they're in conflict, which requires awareness of their own goals, constraints, and the goals of other agents they're interacting with. Detection can be proactive (agents identify potential conflicts before taking action) or reactive (conflicts emerge after incompatible actions have been initiated).

Classification determines what kind of conflict exists and how severe it is. Is this a goal conflict or a resource conflict? Does it involve hard regulatory constraints or soft preferences? Can it be resolved through negotiation, or does it require arbitration? Classification shapes which resolution strategy gets invoked.

Resolution strategy selection matches the classified conflict to an appropriate resolution mechanism. Some conflicts have predefined resolution paths. Others require dynamic selection based on context, stakeholder impact, and system state. This is where your conflict resolution architecture makes its most important decisions.

Negotiation or arbitration executes the selected strategy. Negotiation involves agents proposing, counter-proposing, and searching for mutually acceptable outcomes. Arbitration involves a third party (another agent, a rule engine, or a human) making a binding decision. The choice between these approaches depends on the conflict type and organizational policy.

Execution implements the resolution and coordinates agent behavior accordingly. This phase often reveals whether the resolution was actually workable or if it created new problems downstream.

Learning and policy update closes the loop. Effective systems capture data about conflicts, resolutions, and outcomes. They use this data to refine resolution strategies, update policies, and ideally prevent similar conflicts in the future. This learning component is what separates mature agentic systems from brittle ones.

Rule-Based and Priority-Driven Resolution Protocols

The simplest conflict resolution approach relies on hard rules and deterministic hierarchies. When conflicts arise, predefined priority orders determine which agent's objective takes precedence.

In a rule-based system, you might establish that compliance agents always override operational agents. Safety agents always override efficiency agents. Executive-directed agents always override functional agents. These hierarchies create clear authority structures that eliminate ambiguity.

Priority-driven protocols work well in specific contexts. Regulated environments benefit from clear, auditable hierarchies where compliance always wins. Safety-critical systems need hard rules that prevent agents from even considering unsafe compromises. When stakes are high and precedent is well-established, deterministic resolution provides the right balance of speed and safety.

These approaches have significant limitations. They're rigid by design, which makes them brittle when facing novel scenarios. They don't adapt to context or learn from outcomes. If your rule says "finance always overrides sales," you get consistent behavior, but you might miss situations where a strategic opportunity justifies bending normal risk tolerance.

Rule-based systems also struggle with indirect conflicts. When three agents have partially overlapping objectives and constraints, a simple priority hierarchy may not provide a clear resolution path. You need rules that account for multi-party negotiations, which quickly become complex and difficult to maintain.

Despite these limitations, rule-based resolution should form the foundation of any conflict resolution architecture. For a subset of conflicts, particularly those involving non-negotiable constraints, deterministic resolution is exactly what you want.

Voting and Consensus-Based Resolution Models

When you can't rely on simple hierarchies, voting and consensus mechanisms offer an alternative. These models treat agent communities as decision-making bodies where conflicts are resolved through collective agreement rather than top-down authority.

The simplest form is majority voting. When agents disagree on a course of action, they vote, and the majority position wins. This works reasonably well for peer agent collaboration where no single agent should have authoritative control.

More sophisticated models use weighted voting based on stake or expertise. An agent that has more context about a decision gets more voting weight. An agent that bears more risk from the outcome gets more influence. These weighted systems better align decision authority with decision consequences.

Reputation-based voting takes this further. Agents earn reputation through successful decisions and lose reputation through poor outcomes. When conflicts arise, votes are weighted by reputation scores, creating incentive structures for agents to make decisions that benefit the broader system.

Consensus-based models require supermajorities or unanimous agreement before taking action. These are common in cross-functional workflows where agent teams need genuine alignment, not just majority preference. A product development workflow might require consensus between design, engineering, and business agents before proceeding to the next stage.

The trade-offs here are significant. Voting provides fairness and distributes authority, but it's slower than hierarchical resolution. Consensus models create genuine alignment but risk deadlock when agents can't agree. Both approaches are vulnerable to strategic behavior, where agents vote based on factional interests rather than optimal outcomes.

Voting works best in scenarios where you have peer agent collaboration, no single source of truth, and situations where the cost of getting the "wrong" answer is lower than the cost of top-down decision-making. Cross-functional decision-making, especially in early-stage workflow development, benefits from consensus approaches that force agents (and the humans who designed them) to confront conflicting assumptions.

Machine-Learning-Based Negotiation and Mediation

The most sophisticated conflict resolution approaches use machine learning to enable dynamic negotiation between agents. Rather than following fixed rules or voting protocols, agents engage in adaptive negotiation where they propose compromises, model other agents' preferences, and search for Pareto-optimal outcomes.

Negotiation agents can be trained using reinforcement learning, where they learn strategies that maximize their objectives while maintaining cooperative relationships. Game theory provides the mathematical foundation, helping agents understand when to compromise, when to stand firm, and how to avoid exploitation.

These systems work by having agents exchange proposals and counter-proposals, modeling each other's utility functions, and searching for solutions that satisfy enough of each agent's objectives to be acceptable. A procurement agent negotiating with a finance agent might propose: "I'll defer this purchase by 30 days if you approve expedited payment terms that improve supplier relationships." The finance agent models whether this trade-off is beneficial and responds accordingly.

Multi-objective optimization approaches treat conflict resolution as a search problem across multiple objective functions. Rather than pure negotiation, these systems use algorithms to identify solutions that balance competing goals. A supply chain system might use multi-objective optimization to find inventory levels that satisfy both cost constraints and resilience requirements without pure agent-to-agent negotiation.

The strengths of ML-based approaches are significant. They adapt to context, learn from historical outcomes, and can find creative solutions that fixed rules would never consider. They handle complexity that voting systems struggle with and can operate much faster than human-mediated resolution.

The risks are equally significant. ML-based negotiation can be difficult to explain, which is problematic when stakes are high or when regulatory scrutiny requires transparency. These systems can reinforce bias if they learn from historical data that embedded unfair patterns. They may develop strategies that technically satisfy objectives but violate implicit organizational values or ethical norms.

Most critically, ML-based systems require substantial data to train effectively. Early-stage deployments may not have enough conflict examples to build reliable negotiation agents, which means you need to start with simpler approaches and evolve toward ML-based resolution as your system matures.

Hybrid Conflict Resolution Architectures

The most effective enterprise implementations don't choose between rules, voting, and ML negotiation. They combine all three into hybrid architectures that match resolution mechanisms to conflict characteristics.

A well-designed hybrid system uses escalation ladders that start with fast, automated resolution and escalate to slower, more sophisticated mechanisms only when necessary. Simple conflicts get resolved by rules in milliseconds. Moderate conflicts trigger voting or simple negotiation. Complex conflicts with high stakes escalate to advanced ML negotiation or human oversight.

Here's what this looks like in practice: Your finance and sales agents are in conflict over a discount approval. The system first checks rule-based resolution: Is this discount within pre-approved parameters? If yes, approve automatically. If no, the conflict escalates to weighted voting among relevant stakeholders (sales leadership agent, finance policy agent, customer success agent). If voting doesn't produce a clear outcome or if the deal exceeds certain thresholds, the conflict escalates to ML-based negotiation where agents can propose creative structures. If negotiation fails or if the deal involves strategic accounts, it finally escalates to human decision-makers.

This escalation pattern ensures that routine conflicts resolve instantly while complex conflicts get appropriate attention. It also creates a learning system where patterns that initially require escalation can eventually be handled at lower levels as the system learns.

Decentralized versus centralized resolution is another key architectural choice. Decentralized models let agent communities resolve their own conflicts through peer negotiation. Centralized models route conflicts to specialized resolution agents or governance layers. Hybrid approaches use decentralized resolution for tactical conflicts and centralized resolution for strategic conflicts or those with broad organizational impact.

Why hybrid architectures are emerging as the dominant pattern is straightforward: they balance speed, flexibility, and governance better than any single approach. They let you deploy agents quickly using simple rule-based resolution, then evolve toward more sophisticated mechanisms as your system matures and as you accumulate the data needed to train negotiation agents effectively.

Governance, Trust, and Ethics in Conflict Resolution

Conflict resolution doesn't exist in a vacuum. It operates within governance frameworks, trust requirements, and ethical constraints that shape which resolutions are acceptable and which violate organizational values.

Transparency and explainability are critical requirements, especially as resolution mechanisms become more sophisticated. When an ML-based negotiation system resolves a million-dollar procurement conflict, stakeholders need to understand why that resolution was chosen. "The neural network decided" is not an acceptable answer in most enterprise contexts.

This means building audit trails that capture the full decision path: what conflict was detected, how it was classified, which resolution strategy was selected, what proposals were exchanged, and what data influenced the final outcome. These audit trails serve compliance requirements, enable continuous improvement, and build organizational trust in autonomous resolution.

Auditability extends beyond individual decisions to system-level patterns. Organizations need visibility into how often different types of conflicts arise, which resolution strategies succeed or fail, and whether certain agents or functions are disproportionately involved in conflicts. This systemic view helps identify architectural problems before they become critical failures.

Ethical constraints must be explicitly encoded in resolution systems. Some conflicts have resolutions that are technically optimal but ethically problematic. An agent might learn that offering different prices to different customer segments maximizes revenue, but doing so may violate fairness norms or legal requirements. Conflict resolution systems need hard constraints that prevent agents from even proposing certain types of solutions.

The principle of governance by design applies here. Rather than trying to audit and correct agent behavior after deployment, you build ethical guardrails and governance constraints directly into the conflict resolution architecture. This means defining which conflicts can never be resolved autonomously, establishing clear escalation triggers, and creating feedback loops where resolution outcomes are reviewed against ethical and policy standards.

Trust is the ultimate product of effective conflict resolution governance. Organizations will scale agentic systems to the extent they trust those systems to resolve conflicts in ways that align with organizational values. Building that trust requires demonstrating not just that conflicts get resolved, but that they get resolved in ways that are explainable, auditable, and consistent with how the organization wants to operate.

Designing Your Organization's Conflict Resolution Playbook

Building effective conflict resolution starts with asking the right design questions. These questions force clarity about authority, autonomy, and learning in your agentic architecture.

Who has authority, and when? This isn't just about org charts. It's about defining which agents can override others in specific contexts, what conflicts require human judgment, and how authority changes as situations evolve. A compliance agent might have absolute authority in regulatory conflicts but only advisory authority in strategic planning conflicts.

Which conflicts must never be automated? Every organization has decisions that require human judgment, either because of their stakes, their complexity, or their ethical dimensions. Identifying these boundaries early prevents agents from being deployed in ways that undermine trust. Better to have clear escalation rules than to discover boundaries through costly mistakes.

How do agents learn from failed resolutions? Your conflict resolution system should get smarter over time. That requires capturing data about which resolutions succeeded, which failed, and why. It requires feedback loops that update resolution strategies based on outcomes. And it requires mechanisms for identifying when existing resolution approaches are inadequate and need redesign.

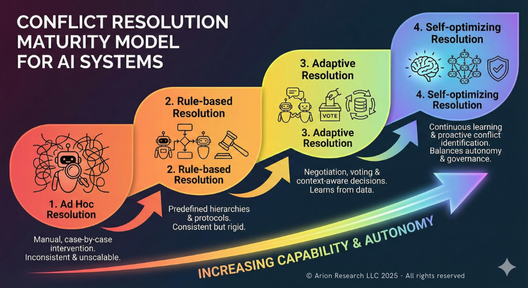

Organizations typically evolve through maturity stages in their conflict resolution capabilities:

Ad hoc resolution is where most organizations start. Conflicts are handled case-by-case through manual intervention. There's no systematic approach, which means similar conflicts get resolved inconsistently. This stage works fine for pilot projects with a handful of agents but breaks down quickly at scale.

Rule-based resolution introduces systematic approaches through predefined hierarchies and deterministic protocols. Organizations at this stage have documented which conflicts follow which resolution paths. This enables faster, more consistent resolution but struggles with novel scenarios and context-dependent situations.

Adaptive resolution incorporates voting, negotiation, and context-aware decision-making. Systems at this stage can handle a wider range of conflicts without human intervention and can adjust strategies based on circumstances. They begin capturing data about resolution effectiveness and can tune their approaches over time.

Self-optimizing resolution is the mature state where systems continuously learn from outcomes, update their strategies, and proactively identify potential conflicts before they occur. These systems balance efficiency with governance, speed with safety, and autonomy with oversight in ways that enable true enterprise scale.

Most organizations should aim to reach the adaptive stage within 12-18 months of deploying agentic systems at scale. Self-optimizing resolution is a longer-term goal that requires substantial data, sophisticated ML capabilities, and mature governance frameworks.

What Comes Next: From Conflict Management to Competitive Advantage

Organizations that master conflict resolution in their agentic systems will have a significant strategic advantage over those that don't. This advantage plays out in three key dimensions.

First, speed to deployment. Companies with robust conflict resolution architectures can deploy new agents faster because they're not starting from scratch on resolution mechanisms each time. They have established patterns, reusable components, and proven strategies that new agents can inherit. This compounds over time. Your tenth agent deployment should be dramatically faster than your first, in large part because conflict resolution is already solved.

Second, operational reliability. Systems that resolve conflicts effectively have fewer failures, require less manual intervention, and maintain stable performance as complexity grows. This reliability is what allows organizations to move from pilot projects to production scale. It's the difference between having a few agents that work under supervision and having hundreds of agents that operate autonomously.

Third, trust and organizational adoption. When business stakeholders see that agents can resolve conflicts in ways that align with organizational values and that preserve appropriate human oversight, they become more willing to expand agent authority and autonomy. Trust enables scale in ways that pure technical capability never can.

Conflict resolution is also becoming a differentiator in agentic platforms themselves. Vendors that build sophisticated resolution capabilities directly into their platforms will win enterprise deployments over those that treat conflict as an edge case. Expect to see conflict resolution emerge as a key evaluation criterion in platform selection over the next 18 months.

The organizations that thrive in an agentic future will be those that recognize conflict not as a problem to be avoided, but as an inherent feature of autonomous systems that must be architected thoughtfully. They'll invest in resolution capabilities early, treat conflict resolution as a core competency, and continuously evolve their approaches as their digital workforces grow in scale and sophistication.

Your agents will come into conflict. The only question is whether you've designed systems that can handle it.