Beyond Bottlenecks: Dynamic Governance for AI Systems

The Coordination Problem

The AI industry has spent years obsessing over intelligence. We measured it in benchmark scores, parameter counts, and reasoning chains. We built models that could pass the bar exam, write poetry, and debug code. But as we move from single Large Language Models to Multi-Agent Systems (MAS), we're discovering that intelligence alone doesn't scale.

The real challenge is coordination, orchestration and governance.

Imagine you've deployed 100 autonomous agents into your enterprise. One specializes in customer data analysis. Another handles inventory optimization. A third manages supplier communications. Each agent is competent at its job. But when a supply chain disruption hits, who decides which agents act first? When two agents need the same resource, who arbitrates? When market conditions shift, how do they reorganize without human intervention?

The question isn't whether individual agents are smart enough. It's whether they can decide who does what without creating a coordination bottleneck that defeats the purpose of distribution.

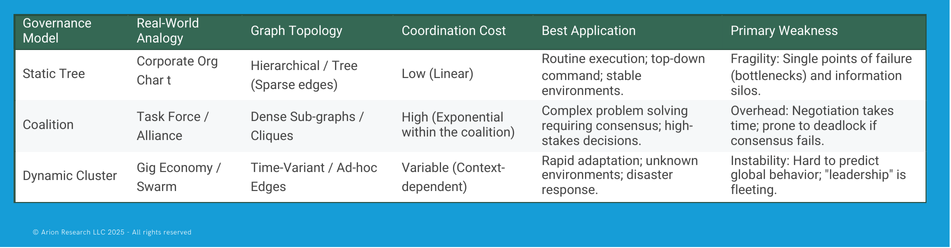

Here's the insight: We can map this problem directly onto human organizational structures. The mathematics of Coordination Graphs gives us three governance models that look suspiciously familiar: the rigid Org Chart, the temporary Coalition, and the fluid Dynamic Cluster. Each has tradeoffs. Each works best under different conditions. And understanding when to use which structure might be the difference between a multi-agent system that scales and one that collapses under its own coordination overhead.

The Basics: What is a Coordination Graph?

Before we dive into governance structures, let's establish what we mean by a Coordination Graph. The concept is simpler than it sounds.

A Coordination Graph is a way of describing dependencies between agents. Each agent is a node. Each dependency is an edge connecting two nodes. An edge exists when Agent A cannot act optimally without considering what Agent B is doing, or when their actions influence each other's success.

Think of it this way: If you have a writer agent and an editor agent working on the same document, they have a dependency edge. The editor can't optimize their edits without knowing what the writer is writing. The writer's effectiveness depends on whether the editor will flag certain style choices. They're connected.

The goal of any multi-agent system is to maximize what we call the Global Utility Function. In mathematical terms:

This looks intimidating, but the translation is straightforward: "How do we make sure individual agent choices sum up to a win for the whole team?"

Each agent has its own local payoff function () based on its action (). The challenge is ensuring that when every agent optimizes for its local payoff, the sum of all those local decisions produces the best outcome for the system as a whole. This is where coordination structure matters. The way you connect your agents determines whether local optimization helps or hurts global performance.

Different graph structures give us different mechanisms for solving this optimization problem. Let's look at three.

Structure 1: The Static Tree (The Corporate Org Chart)

The first coordination structure is the tree. If you've ever worked in a traditional corporation, you already understand this graph topology.

In a tree-structured Coordination Graph, dependencies are fixed and hierarchical. Information flows up. Decisions flow down. Each agent (employee) reports to exactly one parent agent (manager). The parent has multiple children, but children don't coordinate directly with their siblings. They escalate to the parent, who resolves conflicts and issues instructions.

The mathematical beauty of a tree structure lies in an algorithm called Variable Elimination. Here's how it works: Child nodes make decisions and report their optimal actions to their parent. The parent then eliminates those variables from its own decision space (they're now fixed constraints) and optimizes its own action accordingly. This process cascades up the tree until you reach the root node (the CEO), which makes the final coordinating decision that flows back down.

This structure has obvious advantages. It's computationally efficient. The algorithm solves in linear time relative to the number of agents. Accountability is clear. If something goes wrong, you can trace the decision path up and down the tree. The structure is stable. Agents don't need to constantly renegotiate relationships.

But the weaknesses are equally obvious. Trees are brittle. If the CEO node fails or becomes a bottleneck, the entire coordination structure disconnects. Silos emerge because lateral collaboration is impossible without escalating to a common parent. If your marketing agents and your engineering agents need to coordinate, they can't do it directly. They have to route through management layers. This creates latency and filters information.

The tree works brilliantly for routine operations with clear hierarchies of decision-making. It fails when the environment demands lateral collaboration or when the central node becomes overwhelmed by coordination requests.

Structure 2: The Coalition (Political Alliances & Task Forces)

The second structure abandons fixed hierarchy for purpose-driven clusters. In graph theory terms, we're talking about dense subgraphs: groups of agents where most or all pairs are directly connected.

Think of a cross-functional task force. You pull a designer, a developer, a copywriter, and a data analyst into a room and tell them to ship a landing page. For the duration of that project, they form a coalition. They coordinate directly with each other, not through management layers. Every agent in the coalition has edges to every other agent. In graph terms, they form a clique.

Unlike the Org Chart, these connections form based on shared immediate goals. When the project ends, the coalition disbands. The agents return to their normal roles or form new coalitions for different objectives. The structure is fluid in time, though fixed during execution.

The advantage is consensus quality. When agents can negotiate directly, they can find solutions that a hierarchical structure would miss. The coder can tell the designer that a particular layout is technically infeasible before the design is finalized. The copywriter can adapt messaging based on real-time data analysis feedback. This produces better outcomes for complex, creative work.

But there's a cost. Communication overhead scales with the square of coalition size. If you have 5 agents in a coalition, that's 10 pairwise coordination channels. With 10 agents, it's 45 channels. With 20 agents, it's 190. Every agent must negotiate with every connected peer. This is expensive in both compute and time.

In game theory terms, coalitions also introduce the stability problem. You need mechanisms to ensure that every agent stays committed to the coalition strategy. In technical language, you're looking for Nash Equilibrium: a state where no agent has an incentive to defect from the coalition's agreed action plan. Achieving this requires sophisticated negotiation protocols.

The coalition structure trades efficiency for quality. It works when you need high-stakes consensus on complex problems. It breaks down when you try to scale it beyond about 10-15 agents or when speed matters more than perfect agreement.

Structure 3: Dynamic Clusters (The Liquid Network)

The third structure is the most sophisticated and the least familiar. Here, the edges of the Coordination Graph aren't just fluid over time. They change in real-time based on context, proximity, or environmental state.

Imagine a disaster response scenario. You have 50 autonomous drones surveying a search area. At first, Drone A is coordinating with Drones B and C because they're searching adjacent grid squares. But as Drone A moves to a new area, its coordination needs shift. It drops connections with B and C (they're too far away to matter) and forms new dependencies with Drones D and E, which are now in its operational neighborhood.

The graph topology reshapes itself dynamically based on relevance. Agents define their "coordination neighborhood" on the fly. This could be based on physical proximity, task similarity, information freshness, or any other contextual variable.

This is adaptive governance in code. Leadership is transient and meritocratic. An agent might have high degree centrality (many incoming edges) for ten minutes because it has information everyone needs, then fade into the background as context shifts. There's no permanent "CEO" node. Authority emerges based on situational relevance.

The mathematical challenge here is defining the rewiring rules. How does an agent decide when to drop a connection and form a new one? You need algorithms that can assess whether a potential coordination partner will improve the agent's local payoff function more than its current partners. This requires predictive modeling of future dependencies, which is computationally expensive.

When it works, dynamic clustering gives you maximum agility. The system reorganizes instantly to match changing conditions. There's no coordination bottleneck because coordination itself is distributed. No single node can become overwhelmed.

But the cost is complexity. The agents need sophisticated context-awareness. The communication overhead is unpredictable (it depends on how many edges exist at any moment). And debugging becomes difficult because the structure you observe now might not be the structure that existed when a problem occurred.

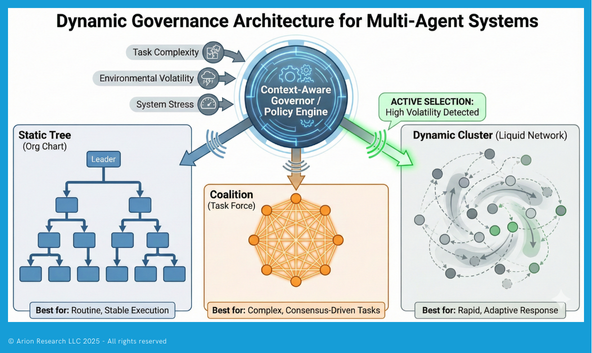

Synthesis: Designing for Shifting Objectives

If you're building a multi-agent system in 2025, you're not choosing one of these structures. You're choosing when to use each one.

The key design challenge is teaching agents to recognize when the governance structure needs to change. This is what I call the "rewiring problem." Your agents need to monitor their own coordination patterns and make architectural decisions about graph topology.

Here's a heuristic that's proving useful in production systems:

Low stress, routine operations: Default to tree structure. You're optimizing for efficiency and predictability. Agents handle standard workflows. Coordination overhead is minimal. Accountability is clear. This is your steady-state mode.

High creativity, complex problem-solving: Shift to coalition structure. When agents face novel challenges that require synthesis of different expertise types, form temporary task forces. Accept the communication overhead as the cost of quality. Dissolve the coalition when the specific objective is achieved.

Crisis response, rapid environmental change: Shift to dynamic clusters. When conditions are changing faster than your coordination structure can be deliberately redesigned, let the agents reorganize themselves based on local context. Accept the complexity as the cost of agility.

The best multi-agent systems aren't one structure. They're metamorphic structures that reshape their own graph topology based on the task at hand. You're building systems that can recognize "we're in crisis mode now" or "this is a creative problem that needs a task force" and rewire their coordination patterns accordingly.

This requires agents that are self-aware about their coordination state. They need to track metrics like: How many coordination messages am I sending per unit of useful work? How long is the decision latency from my requests? Am I waiting on bottleneck nodes? These metrics signal when to shift structures.

Conclusion

When you map Coordination Graphs onto governance structures, a pattern emerges. The Static Tree is monarchy or traditional bureaucracy: stable, efficient, and brittle. The Coalition is parliamentary democracy: high-quality consensus at the cost of coordination overhead. Dynamic Clusters are market anarchism: maximally adaptive but requiring sophisticated participants.

Each structure solves different coordination problems. Trees optimize for routine execution. Coalitions optimize for complex consensus. Dynamic clusters optimize for rapid adaptation. The future of multi-agent systems isn't picking the "best" structure. It's building systems that can shift between structures as context demands.

Here's the deeper insight: As we build digital societies of autonomous agents, we're not inventing new organizational patterns. We're recoding sociology in silicon. Every governance structure humans have developed over millennia has a graph-theoretic analog. Every coordination problem we've solved politically has a mathematical solution in multi-agent systems.

We aren't just building better bots. We're designing the future of work for silicon and carbon alike. And the organizations that figure out metamorphic coordination first will be the ones that actually scale AI from pilot to production.