From "Human-in-the-Loop" to "Human-in-the-Lead": Designing Agency for Trust, Not Just Automation

The Babysitting Problem

Here's a scene playing out in enterprises everywhere: A senior procurement manager, someone with 15 years of experience negotiating multi-million dollar contracts, sits at her desk clicking "Approve" on AI-generated purchase orders. One after another. For hours.

This wasn't the promise of agentic AI.

Companies deploying AI agents are, understandably, terrified of hallucinations, errors, and autonomous systems making costly mistakes. Their response has been to insert "Human-in-the-Loop" (HITL) checkpoints at every decision point. The logic seems sound: keep a human in the process, and you keep control.

But the reality is something different. What organizations have actually created is an expensive babysitting workflow. Highly paid experts spend their days reviewing mundane AI outputs instead of applying their expertise to strategic problems. The AI does the thinking; the human does the clicking.

This approach carries a hidden danger that most organizations haven't confronted. Researchers in automation safety have long documented two related phenomena: automation bias and vigilance decrement. When humans are relegated to the role of passive reviewers, their attention drifts. They begin trusting the system's outputs without scrutiny. They rubber-stamp decisions they should question. The safety mechanism becomes a vulnerability.

If we want to scale agentic AI, we need a different model. We must stop treating humans as safety nets reacting to AI outputs and start treating them as pilots directing AI capabilities. This is the shift from "Human-in-the-Loop" to "Human-in-the-Lead."

Defining the Shift: Loop vs. Lead

The distinction between these two models is more than semantic. It reflects a fundamental rethinking of where human judgment belongs in an AI-augmented workflow.

Human-in-the-Loop (The Legacy View)

In the traditional HITL model, the workflow follows a predictable pattern: the AI acts, then the human reviews, then the action executes. The human functions as a barrier or gatekeeper, positioned to catch errors before they propagate. The primary goal is risk mitigation.

This made sense in an earlier era of AI deployment when systems were less capable and trust was appropriately low. But as agents become more sophisticated, this model creates bottlenecks that defeat the purpose of automation. Every decision, regardless of complexity or consequence, must pass through the same narrow checkpoint.

Human-in-the-Lead (The Agentic View)

The Human-in-the-Lead model inverts the relationship. The workflow becomes: the human sets intent and context, the agent develops a plan, the human refines that plan, and then the agent executes autonomously within defined boundaries.

In this model, the human is the strategist while the agent is the operator. The goal shifts from risk mitigation to augmented capability. The human isn't checking the AI's work; the human is directing the AI's work.

This distinction matters because it changes what we ask of both the human and the machine. The AI must become more transparent about its reasoning. The human must become more skilled at delegation and oversight. Both must develop a shared language for intent, constraints, and acceptable outcomes.

The Cognitive Crumple Zone

There's a concept from aviation safety that applies directly to agentic AI design: the "cognitive crumple zone."

In highly automated aircraft, pilots can spend long stretches monitoring systems rather than actively flying. When something goes wrong and the automation suddenly hands control back to the human, the pilot faces what researchers call "context collapse." They're cold. They have no situational awareness. They must rapidly reconstruct what's happening, why it's happening, and what to do about it, all while the situation deteriorates.

The same dynamic appears in AI agent design. An autonomous agent processes transactions, manages workflows, or handles customer interactions without incident for hours or days. Then it encounters an edge case and escalates to a human. That human receives an alert with minimal context: "Error processing invoice." They must now reconstruct the entire situation from scratch, often under time pressure.

This is where many Human-in-the-Loop implementations fail. They create cognitive crumple zones by design.

The solution is what I call the "warm handoff." When an agent escalates to a human, it shouldn't just signal a problem. It should transfer context, reasoning, and options in a format that allows the human to engage immediately at the strategic level.

Instead of: "Error processing invoice."

The agent should say: "I've processed invoice #4521, but the vendor address matches a region flagged in our compliance database. I've paused payment pending review. Here's the vendor's transaction history over the past 12 months, the specific compliance flag triggered, and three potential paths forward. How would you like me to proceed?"

The difference is that the human can now make a decision rather than conduct an investigation.

The Co-Audit Workflow in Action

To understand why Human-in-the-Loop fails at scale, consider a supply chain scenario.

In a traditional implementation, an AI agent flags a stockout risk and asks a human manager: "Should I reorder 5,000 units of Component X?" The manager, lacking context, must pause everything. They open the ERP system. They check current inventory. They pull up the sales forecast. They verify the supplier's lead time. They cross-reference production schedules.

The AI hasn't saved time. It has assigned homework.

This is the "black box" problem. The agent provides an output without the reasoning that produced it. The human has no way to evaluate the recommendation without independently reconstructing the analysis.

To move to Human-in-the-Lead, we need what I call a Co-Audit Workflow. In this model, the agent doesn't just request permission. It presents a reasoning trace, a structured argument that exposes the logic, data sources, and constraints it used to reach its conclusion.

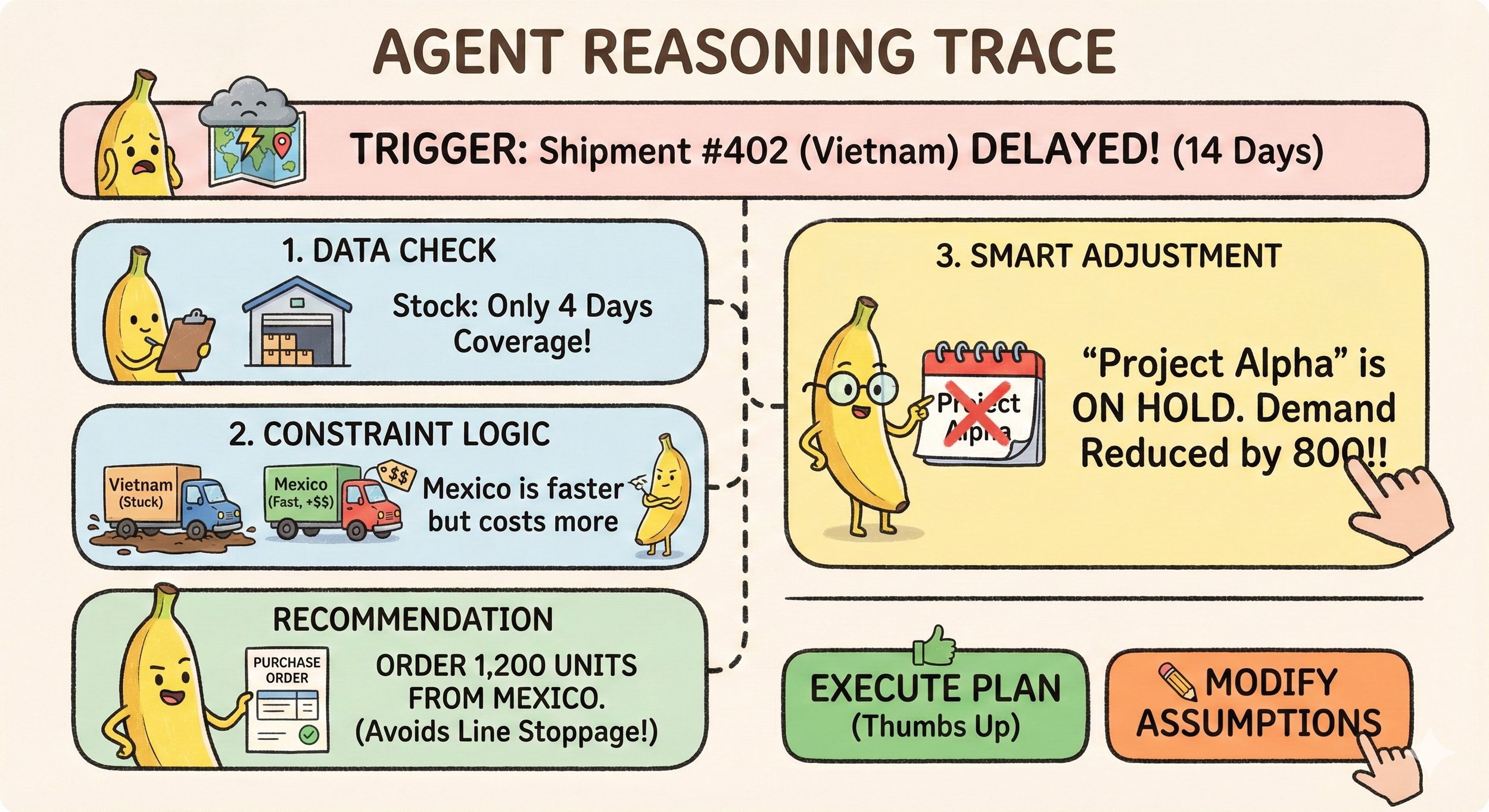

Scenario: A Procurement Agent Faces Disruption

Imagine a procurement agent managing inventory for a consumer electronics manufacturer. A severe storm in Southeast Asia disrupts shipping routes, delaying a critical component shipment.

The Black Box Approach

The agent sends an alert: "Shipment #402 from Vietnam is delayed. I've drafted an emergency order for 2,000 units from our backup supplier in Mexico at a 15% premium. Approve or Reject?"

The human manager hesitates. Do we really need 2,000 units immediately? Is the premium justified? Will the delay actually impact production, or do we have sufficient buffer stock? To answer these questions, the manager must leave the interface and excavate data from multiple systems. Trust remains low because visibility remains low.

The Co-Audit Approach

The same agent, designed for Human-in-the-Lead operation, presents the decision as a transparent stack of logic:

Recommendation: Initiate contingency order for 1,200 units (adjusted from initial estimate of 2,000) from Supplier B in Mexico.

Reasoning Trace:

Trigger: Shipment #402 from Vietnam is delayed 14 days due to weather disruption.

Impact Analysis: At current run rates, Production Line 3 will exhaust component inventory in 6 days.

Inventory Status: Current buffer stock provides 4 days of coverage.

Constraint Analysis:

Supplier A (Vietnam) cannot expedite; port closures continue through next week

Supplier B (Mexico) offers 3-day lead time at 15% cost premium

Production schedule adjustment: Project Alpha entered hold status yesterday, reducing immediate demand by 800 units

Calculated Gap: 1,200 units needed to bridge until Vietnam shipment arrives

Proposed Action: Place order for 1,200 units with Supplier B

Options: Edit Plan | Execute | Request Additional Analysis

Created with Google nano Banana Pro

Why This Changes Everything

In the Co-Audit scenario, the dynamic between human and agent transforms completely.

Verification replaces investigation. The human doesn't need to hunt for data. The logic is visible: Project Alpha is on hold, buffer stock covers four days, the gap is 1,200 units. The human can verify the reasoning rather than reproduce the analysis.

Strategic injection becomes possible. This is where Human-in-the-Lead delivers its real value. The manager reviewing this trace might spot something the agent missed, a soft constraint not captured in structured data.

"Agent, the hold on Project Alpha ends in three days, not two weeks. The production team just confirmed restart for Monday. Recalculate demand assuming Alpha resumes on schedule."

Warm handoffs enable precision correction. Because the agent exposed its reasoning, the human can correct a specific assumption (the project timeline) rather than rejecting the entire recommendation. The agent recalculates, updates the order quantity to 1,800 units, and the human clicks Execute.

This is augmented cognition in practice. The agent handles data retrieval, correlation, and calculation. The human handles nuance, context, and strategic judgment. Trust builds because visibility exists. The human can see exactly where the agent excels and where it might have blind spots.

The Human Element: Training for Orchestration

Shifting to Human-in-the-Lead requires more than technology changes. It demands new skills from the humans in the system.

We are moving from "doing the work" to "managing the worker," even when that worker is digital. This is a genuinely new competency for most employees. They've spent careers developing expertise in execution. Now they must develop expertise in orchestration.

Three capabilities become essential:

Prompting with clear intent. Effective delegation to an AI agent requires the same skills as effective delegation to a human team member, only more so. Ambiguous instructions produce ambiguous results. Employees must learn to specify goals, constraints, acceptable tradeoffs, and escalation thresholds with precision.

Critiquing plans before execution. Strategy means evaluating options before committing resources. When an agent presents a reasoning trace, the human must be able to identify gaps in logic, missing constraints, or flawed assumptions. This is a review skill, not an execution skill.

Auditing outcomes for quality. After the agent executes, the human must assess whether the outcome met expectations and whether the process should be adjusted for future iterations. This is performance management applied to digital workers.

Organizations investing in agentic AI must invest equally in developing these capabilities across their workforce. The technology is only as effective as the humans directing it.

Measuring Success Differently

Traditional automation metrics focus on efficiency: time saved, cost reduced, throughput increased. These matter, but they miss something crucial in Human-in-the-Lead systems.

The metric that predicts adoption and sustained value is confidence. If the humans working alongside agents feel genuinely in control, if they trust the system's transparency and their own ability to direct it, adoption accelerates and deepens. If they feel like babysitters or rubber stamps, they'll resist, work around, or simply disengage from the technology.

Confidence comes from visibility, control, and competence. Design for all three.

The Path Forward

True agency in AI systems isn't about removing humans from the process. It's about elevating humans to the executive level of the workflow, the level where intent is set, strategy is refined, and judgment is applied to novel situations.

The organizations that will capture the full value of agentic AI are those that make this shift deliberately. They'll redesign workflows around Human-in-the-Lead principles. They'll build agents that expose reasoning rather than hide it. They'll train their people for orchestration rather than execution. They'll measure confidence alongside efficiency.

The question isn't whether to include humans in AI workflows. It's how to position them for maximum impact.

Don't build agents that ask for permission. Build agents that ask for direction.